Although the concept is known by many names and iterations, the ideal of unconditional love is universally held in the collective human psyche. Most cultures have religious or philosophical principles that refer to the concept, often presented as the ultimate goal of the human maturation process. Yet, unconditional love is also seen as something that is rarely, if ever, achieved. What is this ideal we’re looking for, and why do we set our sight on something so frustratingly elusive?

Psychologists, philosophers, neuroscientists, and spiritual teachers define unconditional love differently, but it always involves, to some degree, an ideal state of unchanging love. We like to compare it with the romantic idea of transcendent “true love,” although such physical-bound love is temporary and lustful, and it therefore does not qualify for being unconditional. Unconditional love is a pure, unselfish state of love that defies reason, a state wherein a person continues to love even when the recipient seems unworthy or unloving in return.

The Western concept of unconditional love is largely influenced by Greek philosophy and Christian apologetics. In his classic treatise on the topic of love and Christianity, “The Four Loves,” C.S. Lewis identified unconditional love as agape. This word was borrowed from the Greek word for “charity” or the “love of a parent for a child.” In biblical texts originally written in Greek, the word agape is used to connote any kind of selfless love, whether between human beings or between humans and God. Christian theologian Thomas Aquinas was the first to equate it exclusively with divine love, which can only be perfectly demonstrated by God toward sinful humanity. Lewis extends that concept and describes it as the central aim of Christianity. The other types of love identified by Lewis — affection, friendship, and erotic love — are carnal, self-centered, and worldly by comparison, so agape is the only love through which the human mind and soul may be transformed away from what he called “demonic self-aggrandizement” toward a God-like view of the world.

Lewis admits, however, that unconditional love runs completely counter to human nature because the latter emotion leaves one vulnerable in ways that are hard, if not impossible, to bear. But love we must, says Lewis, if we are to find salvation: “To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket, safe, dark, motionless, airless, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. To love is to be vulnerable.”

Essentially, a truly unconditionally loving person accepts the naked emotional vulnerability of love and says, “I love you anyway,” even when it hurts like hell. But this selflessness — like Christ’s giving his life on the cross for the sins of others — is the self-sacrifice required for true spiritual transformation.

Humanistic psychologists agree that unconditional love is necessary for personal transformation, but they usually lighten the concept with the more achievable notion of “unconditional positive regard,” a term coined by the humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers. The idea here is to dampen the human tendency to react negatively to undesirable behaviors in ourselves and others. This begins with the therapist herself, who must refrain from judgmental response to the inner workings of the patient’s mind, so that the patient can express and examine them without fear, even if these thoughts are destructive or immoral. Then, the patient must learn the same unconditional positive regard for him- or herself in order to begin to change, which is impossible without sufficient self-esteem, according to the theories of humanistic psychology. Finally, once some level of healing has been achieved, the patient can transform his or her relationships by practicing unconditional positive regard toward others.

Professor of psychology David G. Myers neatly describes the importance of unconditional positive regard in the therapeutic process: “People also nurture our growth by being accepting — by offering us what Rogers called unconditional positive regard. This is an attitude of grace, an attitude that values us even knowing our failings. It is a profound relief to drop our pretenses, confess our worst feelings, and discover that we are still accepted. In a good marriage, a close family, or an intimate friendship, we are free to be spontaneous without fearing the loss of others’ esteem.”

Psychologist and neurologist Viktor Frankl, however, does not mince terms by calling it “unconditional positive regard.” In his view, “unconditional love” truly is the key, just as the gurus and philosophers teach. Human potential, according to Frankl, can never be attained without reaching for unconditional love. In his classic book “Man’s Search for Meaning,” he writes, “Love is the only way to grasp another human being in the innermost core of his personality. No one can become fully aware of the very essence of another human being unless he loves him. By his love he is able to see the essential traits and features in the beloved person; and even more, he sees that which is potential in him, which is not yet actualized but yet ought to be actualized.” Having survived the Holocaust, Frankl developed this open-minded view despite experiencing the worst of human behavior.

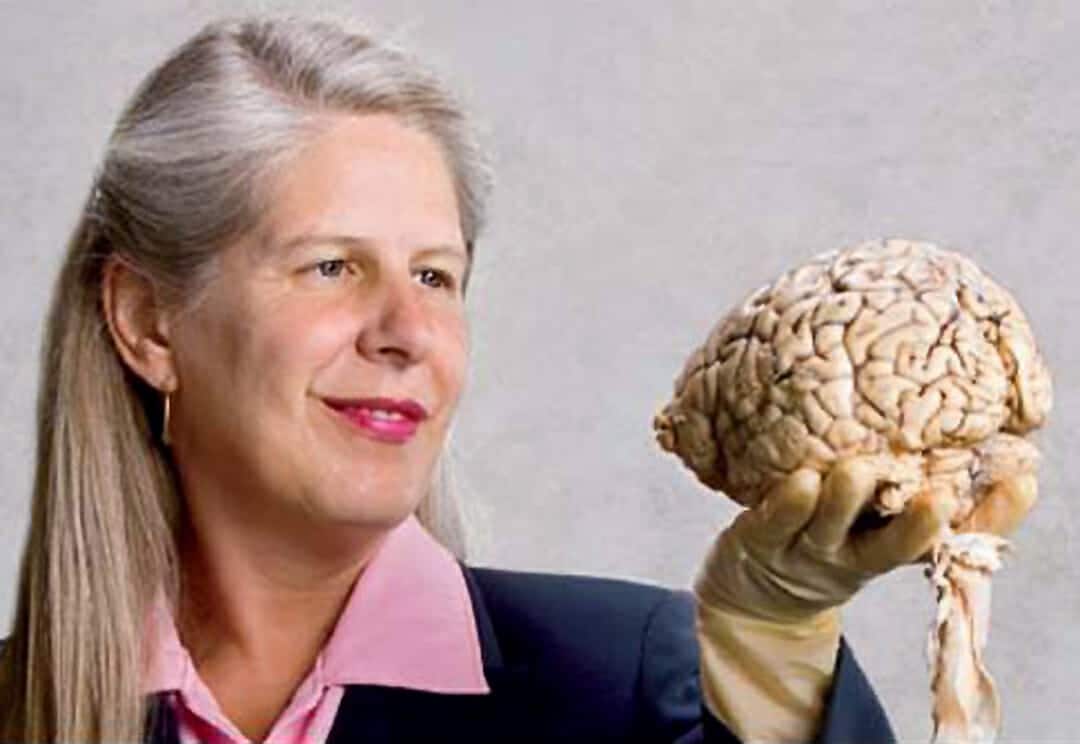

But what does neuroscience have to say about all of this? Science of course avoids the intangible and unmeasurable, so, from a strictly scientific perspective, parts of the discussion are irrelevant. However, some aspects of unconditional love can be observed in the human brain.

In one study published in the journal Psychiatry Research, scientists observed that the brain activated very differently depending on the type of love presented to the study’s subjects; images of “motherly love,” which researchers associated with unconditional love, lit up seven regions of the brain, while images of romantic love only activated three. There was some overlap between the two activated areas, but they were mostly disparate. Subjects were then told to feel unconditional love while viewing pictures of people with intellectual disabilities, which resulted in the same “motherly love” areas of the brain becoming activated, suggesting to researchers that “unconditional love is mediated by a distinct neural network” in the brain.

Likewise, it is well documented that mothers experience a rush of hormones and brain changes during birth that accentuate bonding with their newborn. Any stimulus from the infant, even if seemingly negative, like constant crying or a messy diaper, produces a dopamine (“happy hormone”) rush in the brain and solidifies the habit of attentive care in the mother’s brain. For many years, this was thought to be an automatic part of the pregnancy and birth hormone cycle, but more recent studies have shown that fathers and adoptive parents experience the same brain changes, so long as they have consistent contact with their children.

Parental love seems to be the closest people come to experiencing unconditional love, although parental love is not entirely unconditional because the parent-child relationship is a condition necessary for the newborn’s existence — and parental love is certainly not unchanging, nor is it perfect in every instance. Perhaps this is part of the reason we search for unconditional love, however: our desire to return to the purer love we experienced as infants.

Remember that agape originally meant “parental love” in Greek, and the divine love described by Christianity is equated with God’s undying love for his wayward children, an idea familiar to other Abrahamic religions, too. In Buddhism, a similar concept is taught: In order to achieve the highest expression of unconditional love, called “absolute bodhicitta,” one should imagine having been the mother, in some previous lifetime, of every living being one encounters.

Through the concept of unconditional love, humanity is reaching toward its better self, toward a vision of a world without all the strife and hatred that we associate with human nature. A cynic might say that this ambitious goal is unattainable — that mankind has always been cruel and will always be so. But we hang on to the idea of unconditional love as a beacon of hope anyway. As Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed: “I refuse to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality. I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word.” And so on we march toward this unreachable goal, hoping to someday overcome our lesser selves.

This article was originally written in the Winter 2019 issue of Brain World Magazine.