In Bhattacharya’s experiment, volunteers were each given 30 seconds to read the instructions of a verbal puzzle, and another 60 to 90 seconds to solve it. If they were unable to solve it in the time allotted, a hint would appear. Some volunteers solved the puzzle, others did not; and the EEG predicted who would fall where.

By monitoring their brain waves, Bhattacharya noted an increase of high-frequency gamma waves—similar to the findings of Kounios and Beeman’s experiment — in the volunteers who solved the puzzle through sudden insight. The pattern of activity emanated from the right frontal cortex, a part of the brain responsible for executive functioning and shifting mental states. As previously mentioned, this activity was evident up to eight seconds before the participant realized he had found the solution.

Sheth thinks this could very well be the brain capturing transformational thought, or, more commonly, the aha! moment in action before the brain’s owner is consciously aware of it. But here’s the thing: Between the spikes of gamma waves, the sparks of alpha waves and activity stirring in the cortex, the real question is how we can influence this tendency so that these creative breakthroughs can, well, break through more often.

Relax, unwind, and free your mind from obstruction. We often assume that if we don’t notice our thoughts, they don’t exist, but this is actually when we may be thinking the most creatively. According to a study by psychologist Dr. Andreas Fink and colleagues (as well as results from the former study by Kounios and Beeman), trying to force creative insight can inadvertently stifle your creativity. The more activated the brain is, the more likelihood for it to be distracted, as too much attention can overload our information-processing capabilities. Instead, people are most creative when they are experiencing lower levels of arousal in the cortical areas of the brain. It’s in states of daydreaming and drifting when we are most receptive to new ideas.

Additionally, an fMRI study published in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience reveals that people are more likely to solve problems with insight if they are in a positive mood. Moreover, the fMRI results showed that good mood was associated with greater activity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) — an area that plays a role in a variety of functions, from regulating blood pressure and heart rate to higher cognitive functions such as decision-making, empathy, motivation, and attention. These findings suggest that positive mood alters activity in the ACC, biasing participants to engage in thinking and processing conducive to solving a problem by insight.

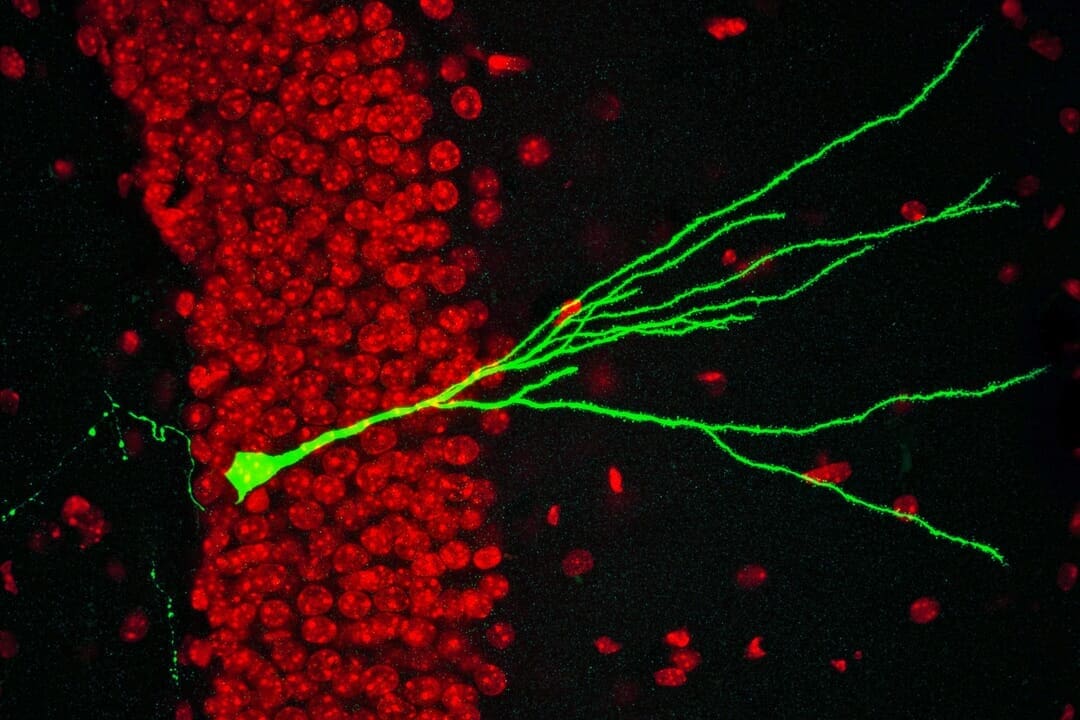

For Steven Johnson, author of “Where Good Ideas Come From,” the secret of generating the aha! moment lies in the notion of “thin air,” which he asserts is anything but. Rather, these moments are actually a relatively predictable outcome that arises from certain preconditions. First, Johnson writes, a good idea is essentially a “network of cells exploring the adjacent possible of connections that they can make in your mind.” Our brain houses roughly 100 billion neurons, with an average neuron connecting to a thousand other neurons scattered across the brain, amounting to 100 trillion distinct neuronal connections. However, since we progressively lose neurons after we hit adulthood, it’s key to keep our brain active to keep the network densely populated. More so, it’s the myriad of elaborate connections and assemblages these neurons form with each other that create ideas and epiphanies. Thus, to increase creative insight, we need to increase new network connections.

How? Well, essentially by acquiring knowledge and skills. This fits with the more established idea that learning and education thwart intellectual decline by building up the brain’s overall capacity for thought — also called “cognitive reserve.”

Second, to create new patterns and connections, which give rise to new ideas, you have to put yourself into innovative environments that foster insightful experiences. These experiences get tossed into our mental reservoir, where they sit and sort of just float around, until one day, they float into just the right alignment to click into a new idea. So, in other words, embrace curiosity. Do stuff. Go places. Collect experiences and gain knowledge. This will be what creates connections that bolster creative insights.

Johnson’s position on fostering good ideas is part of greater concepts called “networked

knowledge” and “combinatorial creativity.” This theory holds that nothing is entirely original; instead, everything builds on what came before. We cultivate ideas by adopting existing pieces of inspiration, knowledge and skill over the course of our lives and recombine them into new creations. In the brain, these new creations are the new neural pathways formed.

Albert Einstein attributed some of his greatest physics breakthroughs to his violin-playing, claiming it connected different parts of his brain in new ways. Renowned novelist Vladimir Nabokov qualified his obsession and knowledge of butterflies to his successful prose. Even Pablo Picasso, who once agreed to quickly sketch a portrait for a woman in the park, claimed that it didn’t take the seemingly few minutes to draw the portrait; it took him his whole life.

And so it comes to pass that these sudden insights, as florid as they seem, are actually the accumulation of certain variables — experiences that form networks, brain chemistry and neuronal connections — and yet, they can be influenced by multiple processes. Though we may not see the aha! moment coming, our brain certainly does.

This article was first published in Brain World Magazine’s Summer 2012 issue.

Related Articles

- Challenging Your Brain for Health and Wisdom

- Find Your Passion and Strengthen Your Brain: A Q&A with Dr. Adele Diamond

- Happiness: The Best Diet You Can Go On

- Moving Up! 5 Ways To Stay Sane Amidst Change

- Old But Not Weak: Mastering Your Body As You Age

- Standing Up for Health: Immobility and the Brain